The history of Greenwood Cemetery is intimately connected with the history of race relations in Tallahassee. Much about the subject is shameful by modern standards, yet all of it is important for a complete understanding of the city's history.

The history of Greenwood Cemetery is intimately connected with the history of race relations in Tallahassee. Much about the subject is shameful by modern standards, yet all of it is important for a complete understanding of the city's history.

Information on this Web page has been abridged and amended from A History of Greenwood Cemetery, Tallahassee, Florida, 1937-1987. This booklet was prepared by Sharyn Thompson, and sponsored by the former Historic Tallahassee Preservation Board of Trustees and the Florida Department of State. (Also see the list of references used in the preparation of the booklet itself.)

Pre-20th Century Practices

During Florida's Territorial and Ante-bellum periods, the black population of Tallahassee and Leon County was made up almost entirely of slaves, although a small group of free people of color did live in the area. In 1830 the population of Tallahassee included:

- 541 whites;

- 381 black slaves; and

- 6 free people of color.

By 1860 these numbers had increased to 997 whites, 889 slaves, and 46 free people of color.

During this time, slaves in rural areas were usually buried on the plantations and farms where they worked. Generally, slave burials took place in segregated graveyards near the family graveyards of the white owners. Markers placed at the graves of slaves were generally ephemeral in nature such as field stones, wooden stakes or crosses, and grave goods which have long since deteriorated or been scattered and lost. Currently, rectangular, grave-shaped depressions in the earth are the only remaining evidence of slave graveyards at most former plantation sites.

In urban areas, slaves and free people of color were commonly buried in segregated sections of public burying grounds, or in cemeteries designated separate from those for white burials. This practice reflected the social structure of the time. In contrast, the burying grounds of the Spanish colonial towns of Pensacola and St. Augustine were probably not sharply segregated until after U.S. acquisition of the Florida Territory from Spain in 1821, because Spanish authorities allowed free people of color some degree of equality.

In 1841, Tallahassee's City Commissioners established Old City Cemetery as a burial place for both blacks and whites. Their burial areas were segregated, however.

After Emancipation in 1865, through the Reconstruction period and well into the 20th century, most black people living in rural areas were buried in churchyards or in family or otherwise privately owned graveyards. In urban areas they continued to be buried in segregated cemeteries.

A second public cemetery (Oakland) was established in 1902, again with separate burial areas for blacks and whites.

Evergreen Cemetery: "Equal," But Separate

The plan to establish a separate cemetery exclusively for black burials was apparently initiated in 1936. In September of that year, City Ordinance 272 established an official cemetery and public burying ground for colored persons of the city of Tallahassee and provided rules and regulations governing burial of bodies of the dead in such cemetery.

Tallahassee Evergreen Cemetery was located near Abraham and Alabama Streets, in the vicinity of the present-day Griffin Middle School. The Ordinance did not state the reason a cemetery was created solely for the burial of blacks. However, opposition to the site was registered by members of Tallahassee's black community. At the City Commission meeting on l3 October 1936:

a delegation of colored citizens consisting of J.R.D. Laster, Annie L. Sheppard, J. G. Riley, Godfrey Wilson and Thomas Morrow appeared...and objected to the establishment of Evergreen Cemetery as a burial ground for the bodies of colored persons in the City of Tallahassee stating that the land upon which Evergreen Cemetery is located is too low for cemetery purposes. The Commission took the objections of the delegation under advisement.

Two weeks later, Samuel A. Wahnish and Guy Winthrop appeared before the Commission and stated "that they had conferred with all the colored people who had objected to the use of Evergreen Cemetery as a burial ground for colored people, and all but one of the Committee were favorable to Evergreen Cemetery; and that the single objector was J.R.D. Laster, colored undertaker."

At the same meeting, City Commissioners moved to tighten control of deeds in the colored section of Oakland Cemetery. If anyone who owned a lot in this section did not actually have anyone buried there, the City would replace the Oakland lot's deed with one for a similar lot in the new Evergreen Cemetery. The unoccupied lots in the black section of Oakland would then revert to the City for resale. The motion was adopted unanimously.

Closed Out of Oakland Cemetery

At the City Commission meeting on l2 January 1937, the "matter of closing the negro cemetery of the old cemetery" was recommended by the city sexton. (Note that the "old cemetery" referred to here was not Old City Cemetery, but rather Oakland.) The City attorney was directed to draw an ordinance:

...requiring that that part of the old cemetery devoted to the burial of negroes be closed unless they can show title to family lots in the said cemetery.

The next day's Tallahassee Daily Democrat reported:

The vexing problem of burial lots for negroes and cemetery regulations, including titles to cemetery lots, is before the city commission again... the commission directed its attorney, James Messer, Jr., to draft an ordinance for early adoption that will regulate the depth of all graves to be dug in the four cemeteries inside the corporate limits. Officials admitted the new law will have a definite bearing on further use by negroes of one of their burial grounds in the city. Recently a new negro cemetery was opened, but members of that race have vigorously protested and so far are said to be almost unanimously opposed to its use as a burial ground.

(The "new negro cemetery" referred to in the above account was the never-used Evergreen, which as stated earlier occupied low-lying ground unsuitable for burial of the dead.)

At the Commission meeting two weeks later, on January 26th, the Ordinance was read in full for the first time (all references to "the city cemetery" are to Oakland):

An ordinance closing that part of the city cemetery heretofore designated as the public burying ground for the purpose of the burial of the dead bodies of colored persons and prohibiting the further burial of the dead bodies of colored persons in said cemetery.

The final vote to pass this ordinance was unanimous.

On 10 February 1937, a short announcement in the Tallahassee Daily Democrat, under the heading "City Closes Cemetery to Burials of Negroes," stated simply:

Municipal authorities have closed the [Oakland] Cemetery to negro burials. Long a public burying ground, the space allotted to negroes is said to be filled.

The Greenwood Cemetery Company

In response to the closure of the public cemeteries to Negroes, members of Tallahassee's black community took steps to provide an appropriate place for burials. On 19 March 1937 the Greenwood Cemetery Company was founded "to acquire land so as to provide a burial place for the dead of the colored race near Tallahassee in Leon County." Among the founders of the organization were J.R.D. Laster (the undertaker whose name figures prominently throughout this period of Greenwood's history), William Mitchell, Erma Jenkins, Sam Hills, Maude Lomas, Rev. Robert L. Gordon, James H. Abner, M. Johnson, and T. H. McKinnis.

According to the Company's charter, "Any colored person of good character and not less than 2l years of age" could become a member of the company "by the presentation of his or her application for membership and the approval of such application by a majority of the Board of Directors." The company purchased ten acres of land, in "that part of the South Half of the Northeast Quarter of the Northeast Quarter of Section Twenty-six, in Township 1 North of Range 1 West, lying East of Old Bainbridge Road." This property -- the future Greenwood Cemetery -- was purchased from Erma L. Jenkins, one of the company's founders, for $10.

Burials began in Greenwood Cemetery shortly after it was established in 1937. The lots and blocks for the cemetery's original ten acres were laid out by Surveyor E. G. Chesley. Bartow Duhart was hired to mark the corners of the lots with metal stakes set in concrete. Over the years various modifications were made to the size and shape of the property and it now encompasses 12.4 acres.

Neglect and Deterioration

Neglect and Deterioration

When the Cemetery Company sold burial spaces it was with the understanding that families of the deceased would maintain the plots. At that time, care of grave sites was regarded as a responsibility that family and friends assumed out of respect for the deceased.

However, over the years descendants moved away, ceased to care for the grave sites, or themselves passed away. Although burials continued, Greenwood began to look neglected and abandoned. Some individual lots and gravesites were cared for, but much of the 12+ acres had no maintenance.

Vegetation was uncontrolled -- tree roots disrupted graves, and tall grasses and shrubs hid them from view. Many of the graves themselves collapsed, leaving gaping holes in the ground; wooden markers rotted away and other markers were slowly covered by debris and earth. Details of lot ownerships and burials were not always accurately recorded.

After the passing away of all of the founders of the Greenwood Cemetery Company, the only continuity provided for the facility was by Mrs. Reather Laster Doyle, the daughter of J.R.D. Laster, who continued her father's undertaking business and sold lots in the Cemetery.

Clean-up and Rededication: The Greenwood Foundation

Greenwood was used for burials by the black community throughout the following decades, but because maintenance was not scheduled for the grounds, the physical condition of Greenwood continued to decline.

In January 1985 a group of citizens met to express their concern about the deterioration of the Cemetery. This meeting resulted in the formation of the Greenwood Foundation, whose purpose was to restore the Cemetery "to a safe and respectable condition." Rev. James Vaughn, Jr. was elected the group's president. One of the first actions the organization took was to raise funds to hire a lawn care company to mow and trim the Cemetery. The members of the Greenwood Foundation also approached community leaders, the Tallahassee City Commission, and the Leon County Commission for assistance.

On 28 May 1986 members of the City Commission discussed options for assisting with the upkeep of the cemetery. Then City Manager Daniel Kleman reported that Greenwood was the only cemetery in the city with platted streets: "other private cemeteries [within Tallahassee's boundaries] did not have a plat on record where the streets had been deeded to the public and accepted by a public body." (Note: a "plat" is a formal property survey kept on file by the City.) It was estimated that $280,000 would be needed to repair Greenwood's streets, paths, and drainage system. The Commission voted to "accept responsibility for the construction and maintenance of the streets and drainage facilities with the provision that perpetual landscape maintenance would be the responsibility of the Greenwood Foundation or others."

Throughout 1986, the Foundation received monies from both the City and Leon County, as well as a commitment from the City to provide cemetery upkeep. In May of 1987, the first clean-up effort by some 200 citizen volunteers resulted in a complete cleaning and mowing of the cemetery's grounds. By late September, following several other clean-up days, the entire area was well-maintained and ready to be acquired by the City.

During the cleanup of the cemetery, a survey of the cemetery's gravemarkers was conducted by volunteers. The survey recorded the inscription of each marker, assessed the physical condition of the marker, and noted the material it was made of and any design motifs. The survey was conducted under the guidance of representatives of the Historic Tallahassee Preservation Board, who held workshops to train volunteers in the proper surveying techniques. The map and information compiled by the surveyors constitute the official records of Greenwood Cemetery.

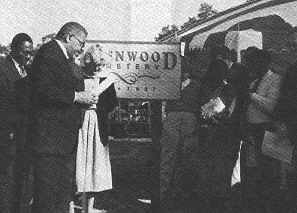

The official rededication of Greenwood Cemetery was held on Saturday, October 10th, 1987. The ceremony included persons involved with bringing the condition of the cemetery to the public's attention, those who participated in its restoration and cleanup, those who recorded its history, and those who were instrumental in having it placed under the City of Tallahassee's jurisdiction.

The official rededication of Greenwood Cemetery was held on Saturday, October 10th, 1987. The ceremony included persons involved with bringing the condition of the cemetery to the public's attention, those who participated in its restoration and cleanup, those who recorded its history, and those who were instrumental in having it placed under the City of Tallahassee's jurisdiction.

In the accompanying photograph, Rev. Herbert C. Alexander (President of the Greenwood Foundation) follows a brief presentation of awards and the unveiling of a new Greenwood Cemetery sign with this rededication prayer:

Before our rededication prayer, permit a brief comment on this moment of rededication at this significant time and place. We close this day now looking to a fuller dawning of a new day.

The impetus and motivation for the rebuilding of Jerusalem's walls in the 5th Century B.C. was due largely to the inspiration of Nehemiah, a servant in the King's Court. "Why is thy countenance sad, seeing thou art not sick?" "Why should not my countenance be sad, when the city, the place of my father's sepulchers, lieth waste, and its gates are consumed with fire?" (Nehemiah 2:2-3)

We have gathered here, but as Abe Lincoln said, "We cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate. The brave men both living and dead have consecrated this place far beyond our poor power to add or detract."

And so, I envision another time, yet at this place, when we shall gather together on an even more significant occasion as one people, one community, united in a purer fellowship of concern. Let us pray:

O God our Father, Eternal and Everlasting,

Thou who stills the tumult of Nations,

And causes lands of sunrise and sunset to be controlled by Thy power.

We thank you for this day and for this occasion:

This rededication of Greenwood.

This rededication of our own sense of self.

May this rededication of Greenwood be a symbol of Thy presence in our lives and in our community. May we see in what we are doing here the far-reaching consequences of cooperation, concern, and goodwill.Yea, even divine hope and inspiration for a better future.We pray, our Father, that a valuable lesson has been learned here and that it has been well pleasing in Thy sight.

Amen.

Historical Significance

When Greenwood Cemetery was established, its founders were acting to provide a place where the dead of Tallahassee's black community could be properly and respectfully buried. For fifty years it was considered a private cemetery, separate from public facilities, and during much of that time it was neglected and discounted. In 1987, after a campaign to restore the site, Greenwood Cemetery was returned to the dignity and grace that its founders had meant for it to carry through eternity.

When Greenwood Cemetery was established, its founders were acting to provide a place where the dead of Tallahassee's black community could be properly and respectfully buried. For fifty years it was considered a private cemetery, separate from public facilities, and during much of that time it was neglected and discounted. In 1987, after a campaign to restore the site, Greenwood Cemetery was returned to the dignity and grace that its founders had meant for it to carry through eternity.

The history of the black community is an integral part of Tallahassee and Leon County's history, and it is vital for understanding and interpreting the history of the State of Florida. Greenwood Cemetery exhibits a rich diversity of grave markers and mid-20th-century burial traditions. The marker inscriptions reveal important information about demography, epidemiology, settlement geography, trade patterns, ethnicity, and attitudes towards religion and death. In addition, the markers reflect the social and economic status of the individuals buried beneath them, and, as importantly, record the social structure of Tallahassee's black community over a fifty-year period.

Marker Styles

Generally, the markers can be divided into three categories;

- Commercial markers of marble or polished granite which are made by professional companies, or, in certain instances, provided by the U. S. Government for military veterans.

- Cast concrete, with the inscriptions incised in the material while it is wet. These are generally inexpensive and provided by a funeral home or a local business.

- Markers of various materials such as wood, metal, or concrete, usually hand-fashioned and decorated by relatives and friends of the deceased. These often display elements of folk art and/or traditions adapted from an earlier Afro-American culture.

The markers of Greenwood Cemetery generally can be interpreted as reflecting the social positions of the deceased, i.e. large, formally designed commercial stones indicating higher status and wealth, and smaller, simple markers, including those that are considered "homemade," indicating lesser degrees of wealth and prestige.

However, it should be noted that not all hand-fashioned markers indicate low economic status. Rather, they are important expressions of Afro-American folk art, with reflections of West and Central African cultural traditions. At the present time, many of the customs are no longer understood, or they have taken on new meanings that are now associated with the Christian religion. Also, as each generation moves farther away from its ancestors, old practices are forgotten and no longer continued.

Academic studies of such traditions have centered on burial grounds in the Georgia and South Carolina low country and in isolated rural areas of what is sometimes referred to as the "Upland South." However, the traditions can be found throughout the South, wherever slavery was approved.

Vestiges of such traditions are evident in Greenwood Cemetery, and the relatively few examples that remain are valuable for interpreting the history and culture of Afro-Americans.

African Burial Traditions Brought to Tallahassee

Examples of folk art and cultural expressions that are evident at Greenwood include crosses fashioned of wood and metal; concrete markers which incorporate pieces of decorative tile and mirrors in their designs; gravestones and slabs painted silver; and gravesites marked by items belonging to the deceased.

The tiles, mirrors and reflective paint are associated with water, due to the old belief that when a person died a river was crossed, or passed over, to the afterlife. The mirrors can also be interpreted as reflecting the mirror image of the world of the living and the world of the dead. Placing personal items at graves also has traditional beliefs based in West African, Southeast Indian, and some European cultures. Such objects were usually valued by the deceased and considered important for rest of the individual's spirit, or were the last objects used in death, such as a bowl or cup and saucer.

A similar tradition, found in all but the newest of cemeteries or "memorial gardens," consists of historical plantings which were done by family and friends of the deceased. The shrubs and flowers not only served to beautify an otherwise forlorn and sorrowful plot, but were symbols of death (or life); Greenwood Cemetery has many individual plantings which represent these beliefs. Crepe myrtle shrubs were once a common plant for graveyards and cemeteries in the South. Evergreen trees, particularly cedars and yew, are symbols of everlasting life, just as the palms are symbolic of resurrection and triumph over death.

A Living Museum of a City's Past

In addition to the many important cultural elements evident in Greenwood, the site also embodies an important part of local history, exhibiting both popular and traditional characteristics. It is an outdoor museum, the markers serving as monuments to individuals who have played pivotal roles in the community's development, and mirroring the societal patterns that have existed in Tallahassee for the past fifty years.

It is the final resting place for many persons important to Tallahassee's history, including Maxwell Courtney, the first black to attend and graduate Florida State University; Willie Gallimore, three-time All-American running back for Florida A&M University's football team and player for the Chicago Bears; James M. Abner, principal of Lincoln High School; and T. M. McKinnis, owner of the Red Bird Cafe.

Bibliography

Primary Sources: Newspapers

- Florida Sentinel

- Tallahassee Daily Democrat (early name for the Tallahassee Democrat , below)

- Florida State News

- Tallahassee Democrat

Primary Sources: Census Records

- 1830 -- Fifth Census of the United States, Territory of Florida, Leon County; National Archives Microfilm No. 19, Roll 15

Primary Sources: Other

Secondary Sources: Books

- Berlin, Ira, Slaves Without Masters: The Free Negro in the Antebellum South. New York: Pantheon Books, 1974.

- Georgia Writers Project, Drums and Shadows: Survival Studies Among Georgia Coastal Negroes. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

- Groene, Bertram H., Ante-Bellum Tallahassee. Tallahassee, Florida: Florida Heritage Foundation, 1971.

- McIntosh, W. R., Jr. (compiler), Laws and Ordinances of the City of Tallahassee, Florida. Tallahassee: Capital Publishing Co., 1906.

- Merritt, Carole, Historic Black Resources: A Handbook For the Identification, Documentation and Evaluation of Historic African-American Properties in Georgia. Atlanta: Historic Preservation Section, Georgia Department of Natural Resources, 1984.

- Vlach, John Michael, The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts (Chapter 9; "Graveyard Decoration"), Cleveland, Ohio: The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1978.

Secondary Sources: Articles

- Dodd, Dorothy, "The Corporation of Tallahassee, 1826-1860": Apalachee , Tallahassee Historical Society, 1950.

- Fenn, Elizabeth A., "Honoring the Ancestors: Kongo-American Graves in the American South." Southern Exposure, 8, Sept./Oct. 1985.